George Foster tensed when he heard the strange voice, and braced for the worst.

“You ruined my life,” the man said.

Foster had his head down, putting baseballs and 8-by-10 photos on a table where he and other former baseball stars prepared for an autograph-signing fundraiser during a spring training game in Arizona a few years ago.

“I thought, ‘I better move back and remember my karate moves. Did I beat this guy up or something?’ ” said Foster, who learned hand-to-hand combat technique from his brother, who taught it in the military.

No, the man said. “You beat my Dodgers.”

“Oh, that.”

That.

The Big Red Machine.

They still remember. They’ll probably never forget. No matter where they grew up watching baseball.

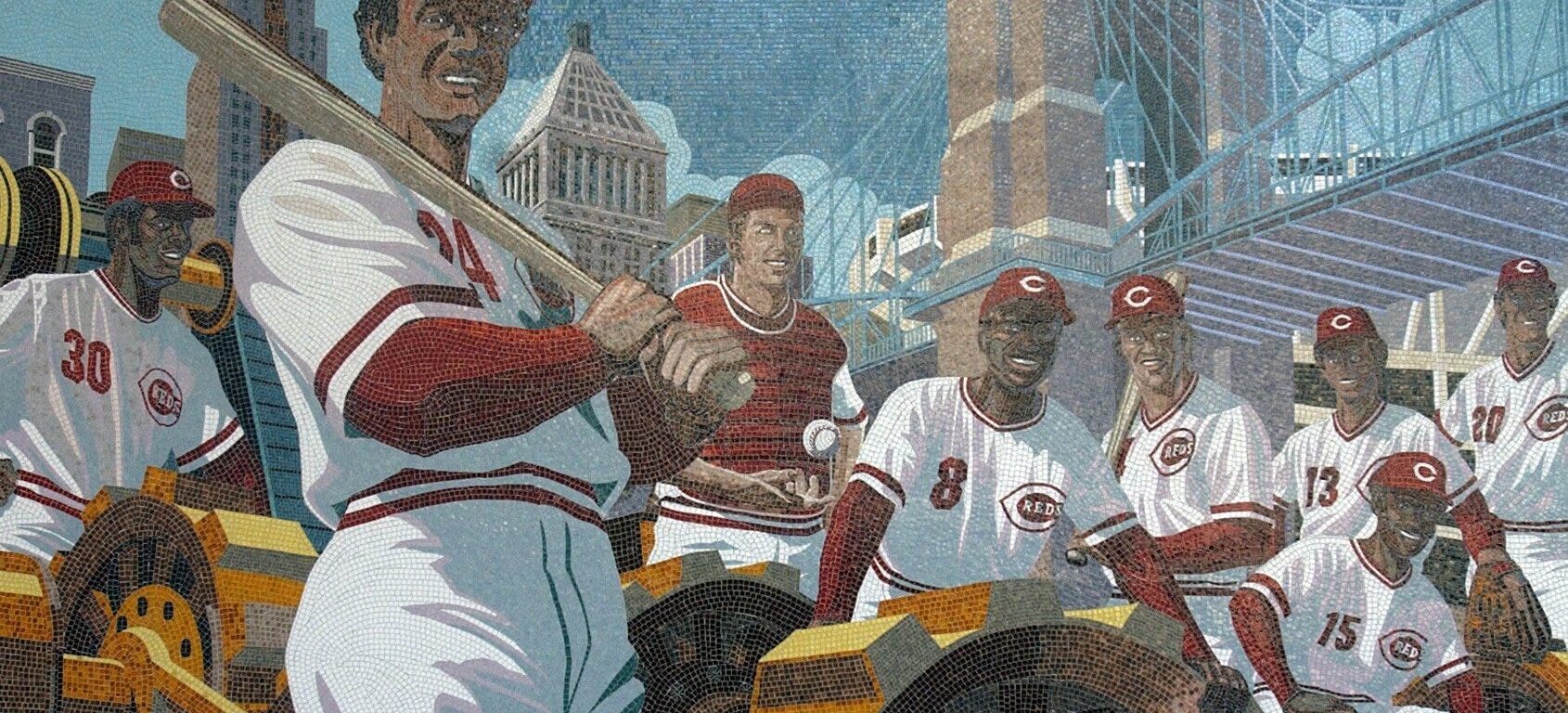

And 50 years later, as nearly all of the surviving members from that iconic team conclude a weekend-long celebration at Great American Ball Park, their legacy remains as unique and intact for its cultural impact on a sport and a city as it does for its staying power.

Never mind the historic dominance of perhaps the greatest lineup ever assembled.

“We captured the imagination,” said Johnny Bench, the Hall of Fame catcher.

Bench recalled the last Big Red Machine reunion just a few years ago.

“You had grandfathers bringing the fathers and the fathers bringing the kids,” he said. “So you had three generations of people coming to the park. And the people that lived our past, they were crying. Because it took them to their childhood and their memories.

“You saw the tears. You saw what it meant to so many people,” Bench said. “We listen to music and we listen to the golden oldies. I guess we were the golden oldies in that way.”

Classic. Harmonic. Hit parade of all hit parades.

The Big Red Machine that dominated much of 1970s baseball certainly hits all of those golden-oldies notes.

But its legacy reaches far beyond that, then and now, for a unique confluence of time and place. Opportunity and vision. Sports and mainstream celebrity.

Big Red Machine legacy rivals any in MLB history

General manager Bob Howsam put his roster together in the last era of true dynasties, the back-to-back championships of 1975 and ’76 coming in the final two seasons before free agency.

They won their division five times from 1970 to 1976, finished second with 98 wins once, played in four World Series in that span, and had four players win six NL MVP awards from ’70 to ’77 (with 14 top-5 finishes overall in that stretch).

And they did it in the place where baseball’s professional roots run deepest, the only place that hosts an Opening Day parade for its baseball team and considers that day a city holiday.

“It’s an amazing story. It’s an amazing team,” Bench said. “I mean, it’s just, like, wow, why can’t you make a story out of the greatness of our team? And if we don’t pass somebody’s muster test, that’s fine. That’s what opinions are for.”

The greatness of the Big Red Machine tells only a fraction of the story of why its legacy resonates with Reds fans, rival fans and even non-fans five decades later.

“It doesn’t just resonate with people that are fans of baseball. It resonates with big leaguers,” said Reds broadcaster Jeff Brantley, the former All-Star closer who led the league with 44 saves for the 1996 Reds. “That’s a whole different kind of ‘resonate.’ “

It’s a legacy amplified by the all-time scandal that followed the all-time greatness of that team: the 36-year saga of hometown hero Pete Rose’s lifetime ban from baseball for gambling on baseball and his posthumous reinstatement last month.

It’s a legacy that includes an all-time actual MLB legacy in Ken Griffey Jr. growing up in the Riverfront Stadium shadows of that team with his brother, Craig, and All-Star dad, and then growing into an inner-circle Hall of Fame centerfielder.

It’s a legacy that 50 years later rivals any team in MLB history, any sports story in local history, and any cultural phenomenon in the region since Skyline Chili or the Roebling Bridge – the names Johnny Bench and Pete Rose becoming so ubiquitous in the national baseball scene that they transcended sports into mainstream American consciousness the way Joe Namath and Willie Mays did before them.

Lasting cultural impact transcends baseball

In Cincinnati, few names in or out of sports carry the same weight all these years later.

“I would say Joe Burrow is probably there,” said Reds reliever Brent Suter, an Archbishop Moeller grad whose grandfather was a police officer in Blue Ash. “Sarah Jessica Parker, Carmen Electra maybe, just in terms of notoriety. They’re right up there with the biggest celebrities.”

Johnny Bench. Carmen Electra. Pete Rose. Sarah Jessica Parker. Joe Morgan, Joe Burrow. Tony Perez, Jerry Springer, George Foster, Dave Concepcion, Doris Day, Sparky Anderson, Steven Spielberg.

It was baseball culture that spilled into popular culture because of the celebrity that spilled into local and regional culture because they played everyday all summer and lived in the community.

It was impact.

“Impact on a city, impact on the game of baseball,” Suter said. “Not to mention Ken Griffey Sr., who was a great player in his own right and had a son who’s maybe the best centerfielder of all-time.”

Legacy.

The Big Red Machine is still the last National League team to win back-to-back World Series, with the Dodgers spending more than $300 million on payroll this year to try to end that reign.

Those Reds had three Hall of Fame players, a Hall of Fame manager, baseball’s Hit King (who may one day join the others in the Hall), four league MVPs, seven All-Stars in their eight-man lineup and five guys with a combined 26 Gold Gloves.

Their heavyweight greatness in their moment was undisputed.

“There were so many different ways that we could beat you,” Foster said. “With our legs, with our gloves, with our bats, with our speed,” Foster said. “Whatever you needed we had on that team. Whatever you needed to be done, we had a guy that could do it.”

Bench said they drew big crowds just for the magnitude of batting practice.They were baseball rock stars wherever went.

“We were intimidating,” Foster said. “We’d go to Dodger Stadium and fans would talk, and then they’d see us come out for (batting practice), and it was like E.F. Hutton. Everybody listens. We go out there, and it would get quiet.”

Until they started taking BP.

“I remember in San Diego, Gaylord Perry told his pitchers not to watch us take batting practice,” Foster said. “We noticed them watching so we started launching. Rose. Bench. Morgan. So now the pitchers were intimidated.”

Yes, that Gaylord Perry. The two-time Cy Young winner and Hall of Fame spitballer. The veteran who in 1971 helped precipitate Foster’s trade to Cincinnati when he confronted the young slugger for taking extra BP with the pitchers.

“Somehow my bat got underneath his chin,” Foster said. “I didn’t know how it got there.”

He was traded quickly after the incident in one of the best trades in Reds history. Or, as Foster heard it from a Giants fan who recognized him a few years ago: “You’re the worst trade in Giants history!”

‘Big Red Machine went out to humiliate you’

They still remember.

That might be the biggest thing 50 years later. Just how deep and lasting the impression those players made was.

“We set the standard,” Bench said.

Just ask the other pitchers in the league.

“They were a different team than every other team I ever faced,” said former Cy Young winner Steve Stone, who faced the Reds nine times from 1971 through ’76 and never beat them (0-4,4.89 ERA). “There were certain teams that if they get up 6-0, maybe they beat you 6-2. If the Big Red Machine got up 6-0, they tried to beat you 12-0. There was never any wasted at-bats.”

Stone pitched in both leagues during his 12-year career and faced the Oakland dynasty in 1973 during its three-year run of championships and later the 1977-78 Yankees champions.

“A lot of those teams could beat you,” Stone said. “The Big Red Machine went out to humiliate you.”

With stars at every position, Stone added. “Not stars but Hall of Famers.”

Who was comparable? Who might have been better?

Not the ’27 Yankees of Ruthian lore, Perez said.

“The Yankees in those days were a great team,” Perez said. “But in those days you didn’t have the great defense. You needed hitters and pitching. That’s all. It’s hard to catch the ball with the gloves they used to use.”

During this recent conversation in the living room of his Miami bayside condo, Perez gestures across the room toward the figurines of the Big Red Machine lineup that he keeps on a top shelf.

“But our team,” he said, “you go through the lineup, that one there, and you can see everything you need to win a ballgame. Anything. You had defense. Speed. Offense. Anything.

“And we had pitching. We didn’t have pitching to win 20 games or something like that. But they were great. The bullpen was great. The starters were great.”

“Not only was that lineup relentless,” said All-Star Rick Monday, who joined the arch-rival Dodgers in 1977, “but defensively they beat you, too.”

Stone called Davey Concepcion one of the most underrated players in the game, an athletic shortstop with five Gold Glove who mastered the skip throw to first, using the hard turf at newly opened Riverfront Stadium to his advantage.

In fact, that Reds “Great Eight” lineup of Rose, Morgan, Bench, Perez, Foster, Griffey, Concepcion and Cesar Geronimo had higher cumulative WAR (wins above replacement), according to baseball-reference.com, than the 1927 Murderer’s Row Yankees of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs and Bob Meusel.

Cincinnati Reds once prototype for best talent in sports

Anyone who wants to win a baseball trivia contest at their next sports-bro party should quiz the room on who the catcher and third baseman were on the ’27 Yankees.

(Bench’s and Rose’s counterparts were Pat Collins and Joe Dugan).

Anybody else?

“Maybe the Dodgers teams (of the 1950s) with Duke Snider and them,” Pete Rose said last year during a long conversation with the Enquirer. “But Duke was the only left-hand hitter on that team. The rest of them were all right-handed hitters. (Pee Wee) Reese, (Carl) Furillo, (Roy) Campanella).”

Anybody else?

Sure, maybe. But consider this in any historical comparison:

Not only did the Big Red Machine rise to dominance in a post-integration, pre-steroids moment, but as a percentage of MLB players, Black American levels were at their highest in the 1970s, more than 20 percent of the league in some of those seasons (more than double today’s numbers). The percentage of Latin American players reached double digits in the ‘70s and grew steadily through the decade.

And the young adults of the 1970s were the kids of the ‘50s and ‘60s, when baseball was still king in American sports.

Bottom line: For the first time – and the last time, so far – the greatest athletes in the Western Hemisphere disproportionately played baseball compared to other sports.

And the Reds were the prototype model for the best of the best of that rich pool of talent.

So if it seems like they had the greatest lineup of all-time, maybe they did.

“Look in the dictionary for ‘the greatest team ever,’ “ Bench said. “We’ll be listed.”

MLB free agency dismantles Big Red Machine dynasty

Two months and a day after the Reds beat the Red Sox 4-3 in Game 7 of an epic World Series, arbitrator Peter Seitz rendered a landmark decision that opened the door to free agency. He ruled that a player who refused to sign a standard one-year contract containing the “reserve clause” that owners had used for decades to retain perpetual club control over players would be deemed a free agent at the end of that season.

“A lot of guys took 20 percent pay cuts in ’76,” said Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer, referring to the maximum one-year cut a team was allowed to impose.

MLB litigated the ruling, but the following August – as the Machine was rolling at the top of the game to another championship – a deal was struck with the players union to create the free agent system that continues into this day and age of $350 million payrolls and $765 million outfielders.

Within months, the Big Red Machine began to be dismantled – first with the November trade to Montreal of Perez and then the free agency departure of ace Don Gullett. Foster, Rose were gone not long after.

And the era of dynasties in places like Cincinnati and Pittsburgh were over.

The Reds’ eight-man lineup of MVPs and All-Stars made a total of $877,000 in salaries in 1975 (roughly the equivalent of $5.3 million today).

Economically, the Big Red Machine had found itself in a sweet spot historically just ahead of free agency.

“That’s why it lasted so long,” Griffey said. “All of us played at least six or seven years with the same team.”

But the top of the Reds organization knew it would be a quick descent from the greatest heights in franchise history as soon as the free agency pact was struck with the union. Even in the earliest days of adjusting to free agency, the Reds quickly pivoted away from some of their higher priced veterans and built a future around the new business strategy. And never sustained more than three or four years of high-level success at a time again.

“Bob Howsam in ’76 had said that,” Foster said. “ ’You won’t see a team like this together again. I think nobody else will equal what we have.’ “I didn’t realize he was going to start breaking up the team.”

Big Red Machine payroll be today? ‘Priceless’

Never mind that a market like Cincinnati could never see another team with the star power and veteran success it had in the 1970s. It’s doubtful anyone could afford to put together the equivalent of that team again – as much as the mega-spending Dodgers and New York teams might try.

“Would you try to pay us?” Bench said.

How much would it even cost?

“A lot – $400 million?” Palmer said.

Even the almighty Dodgers’ almighty dollars might not stretch that far.

“Yes, they would,” Palmer said. “You know what they’d do. It would be deferred money.”

On the other hand, that $400 million estimate might be on the low side, considering the $51 million a year Juan Soto just got from the Mets on his record 15-year deal, or the $40 million Aaron Judge and Alex Bregman each makes this season.

Imagine paying just the hitters on that Big Red Machine team in today’s economy.

Foster: “The word is ‘priceless.’ “

Legendary players remained presence in Cincinnati

Barry Larkin, the Reds’ Hall of Fame shortstop on the 1990 championship team, was a kid in Cincinnati dreaming on that Big Red Machine in the 1970s.

“I remember my mom one time telling me she went to the bank,” said Larkin, who then dropped his voice to a whisper, “and she saw George Foster.”

Larkin laughed.

“I saw George Foster,” Larkin said in a whisper again, imitating his mom’s reverence. “It was a big deal.”

Forget economics. Forget baseball history.

The legacy of the Big Red Machine and all those household names on the city with the annual Opening Day parade was about their impact on the community.

It was a big deal. And 50 years later it still is.

Rose is from Cincinnati. Foster still lives there. Morgan was a Reds broadcaster and a baseball operations advisor until until his death in 2020.

Rose and Bench went into business together with a car dealership while teammates and hosted the local Pete and Johnny Show in the 1980s.

WKRP in Cincinnati debuted in 1978 with a lead actor from Dayton (Gary Sandy) often wearing a Reds jacket he scored from The Enquirer, and Sparky Anderson guest-starring in an episode.

It was baseball culture that spilled into popular culture because of the celebrity that spilled into local and regional culture because they played everyday all summer and lived in the community.

“You used to see the biggest players in the country on the street,” said Jim Tarbell, the longtime civic leader and businessman, who by mayoral proclamation is also known as “Mr. Cincinnati.”

“You’d see Morgan and Johnny Bench. You’d see them at the grocery story,” Tarbell said. “You talk about hometown. It was the epitome of hometown, that period. Civic pride at that time I think was just overwhelming.”

Thanks in large part to a certain group of bigger-than-life baseball players in the provincial river city at the crossroads of Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.

A phenomenon of national celebrity? Something that brought the spotlight on the city culturally? A landmark event or person, place or thing that significant in a moment in time for Cincinnati?

“I’m not sure there’s anything quite as unique,” Tarbell said.

Impacting generations of players from Cincinnati

Larkin is quick to bring up that team when asked why the Cincinnati area has disproportionately produced as many major leaguers as it has compared to other regions of the country – including David Justice, Kyle Schwarber, Andrew Benintendi, Larkin and Suter since that team roamed the city’s streets.

Suter recalls a family story his dad tells of his grandpa helping Perez’s wife, Pituka, with a car problem in his duties as a Blue Ash cop.

“As a thank you, Tony Perez had my dad and his family down there to Riverfront, and they were in the tunnel after the game,” Suter said, “and Tony came out and introduced them to Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, George Foster – all the guys. He was 10 years old. You talk about star-struck.”

You talk about impact.

In local sports, Oscar Robertson was a three-time national player of the year on the UC basketball team in the late 1950s and later an MVP for the Cincinnati Royals in the 1960s.

“I wouldn’t compare life on the street then to the way it was with the Big Red Machine,” Tarbell said.

The Bengals have been to three Super Bowls but haven’t won any, and Burrow is a bona fide national figure.

But no.

“There isn’t any in our lifetime that rivals that,” Tarbell, 82, said.

Beyond sports, as a cultural phenomenon in the city?

There’s the region’s Underground Railroad legacy. The shift to a charter system of governance in the post Boss Cox era a century ago. WKRP in Cincinnati?

You start to get the idea of how unique the Big Red Machine legacy on the city’s landscape might be for its national notoriety and lasting impact.

Tarbell takes a few moments to consider what compares.

“In terms of culture, Fountain Square. She’s still there,” Tarbell said.

And they still remember. Fifty years later.

“It’s a long time,” Perez said.

And it’s yesterday for those who were there the night the champagne poured in Boston.

“I can still see and feel the moment of walking in the clubhouse in ’75,” Bench said, “and seeing Merv (Rettenmund), (Terry) Crowley, (Bill) Plummer and Doug (Flynn), and just sitting there on the side. Just reveling in the whole excitement that was happening with the champagne flowing and Pat Zachry with a grin from ear to year. And from (clubhouse manager) Bernie Stowe and from (trainer) Bill Cooper.

“I mean it was the thing. It was like 25 players. No matter what you did, if you hit three home runs or 50 home runs, you were a world champion. The trainers, the equipment men, the coaches. I mean, (coaches) George Scherger and Alex Grammas and Larry Shepard – I mean, the emotion they were experiencing.”

And then Bench compared it to stories he’d heard about families from Boston who lived thousands of miles away sharing the 2004 curse-busting World Series celebration with their kids.

“The emotional side of it is not just for us,” Bench said. “It was for the thousands and the millions of fans that we created for the Big Red Machine.”

This story is part of an ongoing Enquirer series this summer examining the legacy of the Big Red Machine 50 years after the first of back-to-back World Series titles.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Big Red Machine has lasting cultural impact on city, baseball