Researchers at the University of Waterloo have new designs for urinals they say reduce the amount of splatter or “splashback” to just 1.4 per cent of the standard public model.

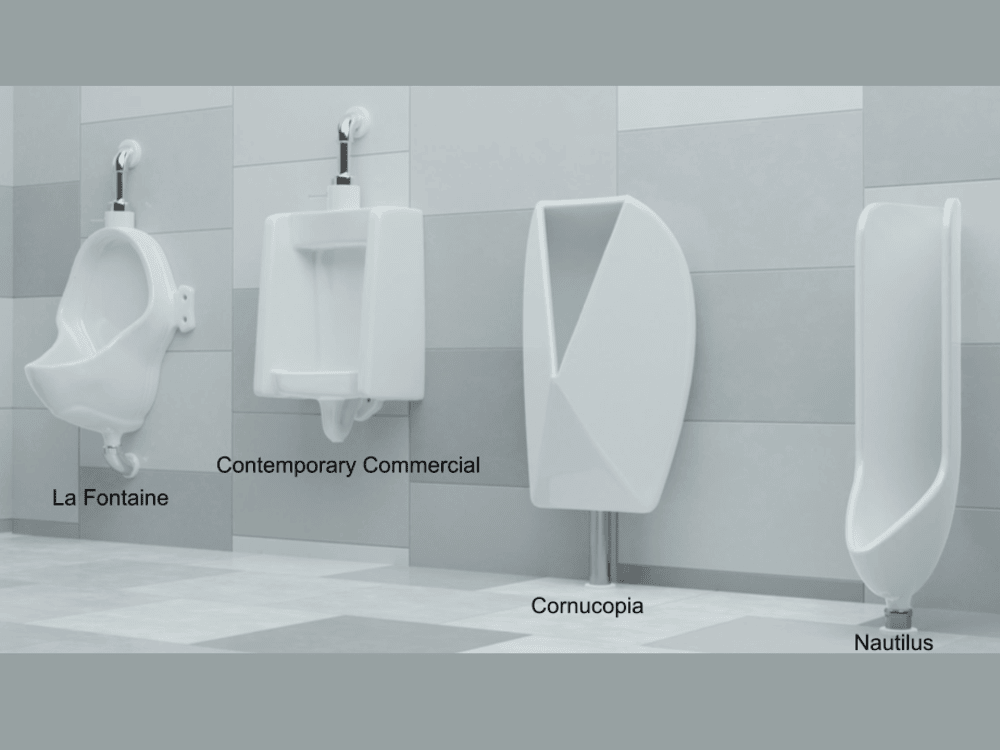

Dubbed the Cornucopia and the Nautilus, the urinals are designed so that the “impinging stream angle” remains below 30 degrees, significantly reducing “the flow rate of splashback under human urination conditions.”

, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering at the University of Waterloo, said the idea came to him and colleague

one afternoon after nature called.

“I noticed that after he used the washroom there’s a lot of splatter on his pants and shoes,” Pan said. “We were thinking: How can we prevent this mess?”

Changing the viscosity of urine wasn’t an option — though it’s wonderful that they considered it — and so changing the shape of the receptacle seemed like the next best choice.

They were inspired by nature as well as daily life. On the latter front, Pan noted that water from a kitchen faucet will sometimes splash back violently from dishes during washing. But reduce the angle to less than 30 degrees and the splash goes away.

Dogs were another source of information: The team noticed that when they pee on trees, they seldom get hit by the splatter.

“What the dogs do is very smart,” said Pan. “By minimizing the impinge angle they can keep their fur clean.”

The researchers wrote that urinal design, which stretches back

to Sri Lanka, “has remained stagnant for over a century.” Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 sculpture of a urinal, titled Fountain, can be seen in art museums in Philadelphia, San Francisco and London, but would not look out of place in the restrooms there.

In research that can not have been glamorous, they found that existing urinal designs create something on the order of a million litres of splashback every day in the United States alone. That’s about 18 mL for each urinal on average, multiplied by the country’s 56 million installations.

They quoted a

that estimated an annual cleaning cost of $122,418.18 per bathroom for 2020 through 2024. “Using the cost per bathroom associated with the Toronto subway as an estimate, up to around $10,000 per bathroom could be saved annually,” they estimated, with savings in water, solvent, tools and labour.

Other solutions have been proposed to deal with splatter, although many come down to maintaining proper aim, and don’t directly deal with the issue of splashback. In 2013, urinals in

were decorated with a life-sized image of a fly in the bowl, on the assumption that users might aim for it and not miss the receptacle entirely.

“Urinal screens and mats have been developed to attempt to mitigate this problem,” the researchers wrote, but such after-market techniques don’t reduce splashback at the source. The Cornucopia and the Nautilus do.

The math is a little complicated, but the researches developed equations for the amount of splashback, which they dubbed Q* (and not, unfortunately, P).

Reducing the value of Q* meant creating a surface that would allow urine to strike it at less that a 30-degree angle, both “where bladder pressure and, consequently, jet velocity are high and the stream is almost horizontal,” and also for “the trajectory of a droplet train at the end of the urination, when the droplets fall almost vertically.”

They added: “The goal is to design curve(s) z=f(r) that intersects z=g(r) by (slashed zero) for arbitrary k, which can be modeled by the ordinary differential equation.” Easy peasy.

Real-world tests did not involve the male members of the team drinking lots of fluid, but instead used “a urination-simulating apparatus … with an anatomically accurate urethra geometry, pump, flow rate meter, flow totalizer, and valves.”

Then there was the issue of creating test urinals of various shapes and sizes, and one store-bought one for control purposes. The researchers photographed and filmed their tests using coloured water, with kraft paper positioned to absorb the splatter.

Pan said the winning designs were called Nautilus and Cornucopia, after the natural shapes of a shell and a horn. The team wanted to go with “Nauti-loo” and “Cornuco-pee-a,” but Oxford University Press, which published the study, wasn’t having it.

That might explain why at no point does the paper, titled

use the word “pee.” The closest it gets to scatological terminology is “pissoir,” the French term for outdoor urinals, which also go by the name “vespasienne.”

One pun that did make it into print was for a hypothetical “hostile anti-urination surface.” Since a low angle minimizes splashback, the researchers realized, a high angle would maximize it.

“Although not suitable as a commonly practical urinal,” they wrote, “it showcases the design philosophy. Such a surface could be installed outdoors to deter public urination, as the offender would fall prey to enhanced splashback. This hostile surface may be dubbed as ‘urine-no.’”